These Tiny Claws Could Improve Drone Landing And Takeoff

We’ve written before about the concept of “biomimetics” – the school of thought that believes technology should be created to imitate natural functions and processes. In our line of work, it mostly refers to drones that attempt to improve efficiency by copying the work of natural evolution, as seen in test products like the DelFly Nimble, which flaps its wings like an insect.

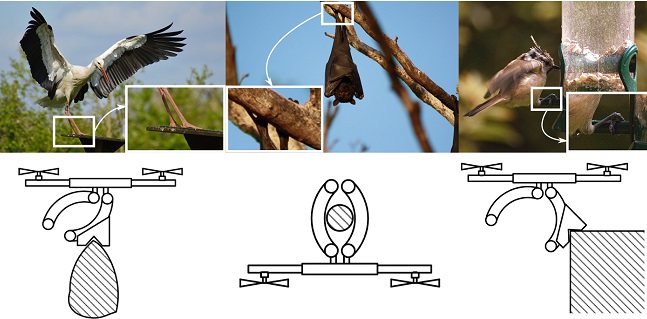

Now, researchers at Yale, led by a postdoctoral student named Kaiyu Hang, have made a drone with tiny claws that perches like a bird or bat.

The claws themselves, or “contact modules” (as Hang refers to them in the paper published in Science Robotics) are 3D printed attachments tipped with 3 controllable fingers. This allows the drone to grab onto anything smaller than its opening width – which could include branches, signs, lamp posts, etc. It can also rest on a stick or grasp a rod to hang upside down like a bat. The latter is shown in the video below:

Why would researchers do something like this? Well, one of the biggest problems facing modern drone technology is the issue of energy consumption. As anyone who’s used a drone knows, batteries tend not to last very long when they’re made small enough and light enough to fly. Worse, these small batteries have to be draining constantly because constant motor action is necessary to create lift.

And while this is a problem in all fields of drone use, it’s especially an issue in the realm of aerial surveillance and mapping, which requires drones to fly over or around an area for long periods of time. It’s this specific issue that the contact modules are designed to help with. When hooked onto a ledge as shown in the first video, the drone can shut off two of its four propellers, using 45% less energy. When grasping a rod as shown in the second video, it can shut down ALL rotors and use about 95% less energy (the last 5% is necessary for the camera and other autonomous functions.) And when perched on a stick with the propellers running slowly, the quadcopter can use 69% less energy.

In Hang’s own words: “perching and resting can provide lower power consumption, better stability, and larger view ranges in many cases.” He also adds that giving drones this kind of grip can also enable greater lifting strength and safer interactions with humans.

The team first tried to execute the idea of perching through dry adhesive and small needles, but these methods only work for small, extremely lightweight UAVs that are specifically designed to use them. Most “gripper” approaches, inspired by bird feet, only allow for perching on cylindrical structures of a certain diameter. These contact modules, once perfe ed, can be 3D printed by anyone and applied to any quadcopter with four legs, and will hopefully not have to worry about the diameter or orientation of a perching surface.

Hang and his fellow researchers have already put drones with contact modules through a variety of tests described in the full research paper and were able to perch successfully on a variety of surfaces. They also found that the drones were able to partially or wholly power down without falling off of their perch, which is essential for the energy consumption that makes these drones worth using in the first place. The team’s next challenge is equipping these drones for real-life conditions. What happens if the drone tries to perch on a surface that’s wet with rain, for example?

So while it may seem silly, perching drones could also be the future of long-lasting aerial surveillance.